Leverage: A Force for Good and Evil

Share

Leverage became a bogey word during the global financial crisis of 2008. The world’s banking system teetered on the edge of collapse as asset write-downs ricocheted from one financial institution to the next, threatening insolvency for all. Leverage was a prime culprit because it amplifies losses as prices fell.

Essentially “levering” or “gearing” means gaining access to an asset’s stream of returns without paying for it outright, either by borrowing money or using derivatives. Leverage allows us to “time-shift” spending so that money can be invested before it is saved.

An everyday example of leverage is a standard mortgage. If house prices rise, both lender and borrower are happy – indeed we congratulate ourselves for investing wisely. Problems arise when prices fall. Even now that mortgages offering more than 100% of purchase value have been consigned to history, buying a house with a 90% mortgage still amounts to 10x gearing. Prices need only fall 10% for the buyer’s initial equity, their deposit, to be wiped out, as was commonplace in the house price crash of the early 1990’s.

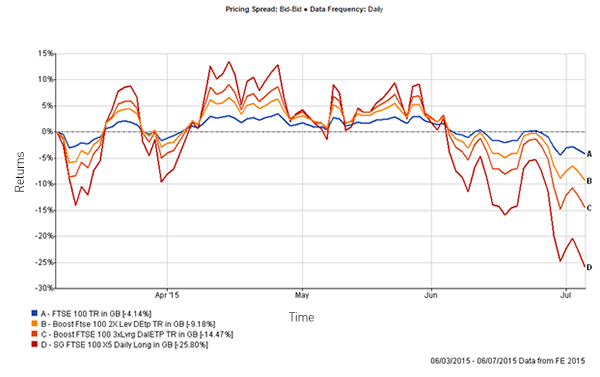

Volatility increases dramatically the more leverage is in place in a market. The following chart shows the FTSE100 index against three Exchange Traded Funds respectively geared to offer 2x, 3x and 5x its daily returns – or 2x, 3x and 5x its daily losses.

What is clear from the chart (Source: FE Analytics: see opposite) is that when things are going well leverage feels great. When the market movement turns against you, it is a disaster.

Arguably leverage is a key part of our capitalist system, allowing capital to be allocated to those who can use them most productively. Where leverage is used prudently it is hugely beneficial: companies are able to fund projects by borrowing the money needed to get started; students are able to fund their education and enter the professional world; hardworking families can get on the first rung of the property ladder. Even derivatives, and the leverage they allow, are not inherently problematic. They can be used as insurance policies, offsetting positions that present an uncomfortable risk but which cannot be sold immediately.

It is when leverage is used only for speculative purposes and without prudential oversight – to turbo charge returns on both the up and downside – that it becomes dangerous. The current case study is China, where authorities have been forced to forbid sales by holders of more than 5% of a company’s shares and to reduce margin payments to prevent the total wipe out of small investors who geared up into their equity bubble this year.

While we may watch, aghast, at the desperation such a measure implies, the Western world wallows in its low interest rate mire. During the Credit Crunch, central bankers forced interest rates down to avoid mass loan defaults and bank collapses, to stimulate the economy with cheap money, and to avoid the social disasters that followed those high minded decisions after the 1929 credit bust to take a stand against moral hazard and allow the banks to go bust.

Initially, after our latest credit bust, both corporations and households did begin to save and reduce their leverage. But perversely, “cheap” debt has incentivised corporations to gear up, not to invest or to expand and recruit, but to buy back their shares in the stock market, boosting investor returns on equity (and stock options), and perhaps betraying a fundamental lack of real, long term confidence.

Similarly, the strong desire for yield, especially from small investors no longer getting any meaningful return on their savings, has encouraged bond managers to buy ever riskier tranches of debt. This risk-blindness is one reason why few central banks have dared raise rates to date: they fear triggering the collapse in confidence which quantitative easing has so far, so successfully deferred.

Like many things in life, there are two sides to leverage, a good and a bad side, and it seems yet another area in which humans, as investors, exhibit their extreme tendency for over-confidence. Our challenge is to see these tendencies for the weaknesses that they are and to judge when we have had too much of a good thing.

Published on 17th July 2015 by Emily Booth, Parmenion Investment Management.

Share

Other News

Finura in the Spotlight: Shortlisted for Multiple Awards

Finura has an exciting few months ahead, as we wait to see the outcome of a number of short listings in different awards categories. MONEY MARKETING AWARDS – Advice firm of the year The winners will be announced on 12 September 2024 at The Londoner Hotel in London https://moneymarketingawards.co.uk/2024/en/page/shortlist-2024#adviser MONEYAGE AWARDS – Financial Adviser Award: […]

5 Tips For Parents With Children Heading To University

Starting university can be a challenging transition, but with a few lifestyle changes and careful planning, it can be a much smoother and enjoyable experience.

Empowering Yourself For Your Future: The Importance Of Lasting Powers Of Attorney (Property And Financial Affairs)

Life is unpredictable and unforeseen circumstances can sometimes leave us incapable of making decisions about our own affairs. That’s where a Property and Financial Affairs Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) comes into play.